In many ways, we are living in a golden age when it comes to all things dry eye. Indeed, there are few areas in medicine with more active research; many millions of dollars have been invested in the search for better ways to treat dry eye disease (DED). Naturally, to effectively treat any disease, it is first necessary to accurately make the diagnosis. Here, too, great strides have been made over the last 10 years.

As we begin our examination of best practices in the diagnosis of DED, we should be sure that we agree on what “best practices” means—and, just as importantly, what it does not mean. We often see “best practices” (BP) used interchangeably with “standard of care” (SOC). This is inaccurate, and in some instances can lead to troublesome misunderstandings. “Standard of care” is a legal term that identifies what a reasonable practitioner with a particular level of training would do in a given circumstance. It is a minimum standard expected in the clinic or in the operating room.

On the other hand, BP can be thought of as the most current, state-of-the-art methods for the diagnosis and treatment of a particular medical condition. Think of BP as the cutting edge of medical care: proven in the field, but perhaps not yet widely adopted. One assumes that BP provides either more accurate diagnosis, more effective and accessible treatment, or both. Our challenge when trying to apply either SOC or BP in DED is that we do not have a consensus on the definition of either in the dry eye world. The subspecialty of dry eye care is simply too new and is changing too rapidly.

If someone were to insist that I declare what constitutes BP for DED, I would offer this: As a rule, every optometrist or ophthalmologist who examines the front of the eye should look for the presence of DED, and if found, should treat it.

With that in mind, it is helpful to think about BP in terms of the type of practice we wish to equip and train. In so doing, I segregate practices into the following categories: comprehensive care, DED specialty care, and cataract/refractive care. Some of the diagnostic basics included in BP today apply to all 3, of course. The cataract/refractive practice will have a couple of specific additions to their armamentarium, and the tertiary DED practice will have some version of everything.

Comprehensive Eye Care Practices

Every encounter starts with the patient history or history of present illness (HPI). As simple as it seems, the first diagnostic test is the DED questionnaire. It doesn’t matter which you choose to use, but each practice should routinely use at least 1 with every DED encounter. Doing so allows you to gauge the severity of your patient’s DED symptoms and to assign a numerical value to them. As you move forward with their care, utilizing a questionnaire allows both you and your patient to more accurately assess whether your chosen course of treatment is working. I like the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) test because of its utility in determining the possible need for in-office treatments, but the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), the Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye test (SANDE), and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) survey are all effective.

Every eye specialist has a slit lamp in the exam room, and we use it to look at every patient. Best practices start with the ASCRS dictum “push, pull, look up,” to which we must now add “look down.” Push on the lower lid to assess meibomian gland secretions. Pull the lid to evaluate position and tension. Look up to examine the fornix and look down to check for the presence of collarettes (which signify Demodex infestation). Every eye should be stained with a vital dye. Best practice is simply fluorescein, but some would argue that the additional information about conjunctival staining gained with lissamine green is better. Once dye is instilled, the tear meniscus and breakup time must be assessed.

DED Specialty Practices

Here we start to see the trifurcation of practices. Advanced DED and cataract/refractive practices need to be sure they don’t miss the presence of DED in the absence of common symptoms and typical objective findings. Studies1,2 show that more than 80% of cataract patients with DED have no symptoms, and many show no evidence in the slit lamp.

This is where tear osmolarity (TO) testing is necessary. In the United States, the only TO test currently available is the ScoutPro by Trukera, now owned by Bausch + Lomb and offered through their surgical division. (Trukera’s previous test, the TearLab Osmolarity System, was discontinued in September 2023.) Tear osmolarity that is elevated (>308) or asymmetric (inter-eye delta >8 regardless of level) is indicative of DED.

In the advanced DED practice, TO not only uncovers “covert” DED, but the results can also lead to a more accurate diagnosis of the type of DED that is present. For instance, a low but highly asymmetrical TO in a symptomatic patient raises suspicion for evaporative, rather than aqueous-deficient, DED. Determining the predominant force behind a patient’s DED typically leads to earlier treatment success with fewer interventions.

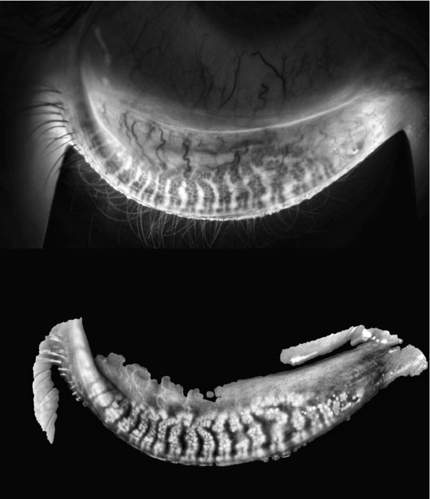

It is also vital that any practice providing care beyond basic DED treatment obtains images of the meibomian glands. At least 85% of DED patients have a component of evaporative DED underlying their symptoms.2 It is not enough to simply look at the lids and try to express meibum from the glands; BP require that you look at the glands themselves. Doing so allows you to evaluate the quality of the oil in the glands and to determine the presence and severity of gland orifice obstruction.

Multiple instruments are available for this task. LipiView and LipiScan, both from Johnson & Johnson, were the first to provide high-quality gland images. More recent additions, such as the Meibox (Box Medical Solutions), a slit-lamp-mounted infrared camera; the Bruder Ocular Surface Analyzer (BOSA, M&S Technologies); and the OMNICAD infrared camera (Lumibird Medical), take very good images of the meibomian glands. The BOSA and the OMNICAD also give an objective measurement of the percentage of gland loss, which can be used to follow the disease over time.

Cataract/Refractive Surgical Practices

DED is a well-known cause of post-surgical refractive surprises. Best practices for pre-op include diagnosing and treating even the mildest cases of DED.

Preoperative TO testing is necessary to avoid missing potentially treatable DED for the cataract/refractive practice. Knowing the TO post-op can also be helpful when one encounters the unhappy 20/20 patient, since elevated TO in and of itself can cause light scattering that is as significant as that found in a 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataract.3

Corneal topography also has become part of the BP in the pre-op evaluation of patients who are considering multifocal or extended depth of focus IOLs. Since intermittent blurred vision is a classic symptom of DED, it is necessary to determine if blurred vision is primarily due to DED. Here, too, topography is a part of BP. Almost any instrument will do, but those that include Placido images showing irregular “mires” are somewhat more helpful as they reveal visible distortions on the ocular surface.

Truly cutting-edge BP is dynamic keratometry, which brilliantly illustrates the changes in the refractive characteristics of the ocular surface over time. Instruments with this capability include the iTrace from Tracey Technologies, the M&S BOSA, and the Oculus Keratograph 5M.

Summary

Best practices in diagnosing DED include some of our most basic tasks: asking your patient to look down when you are at the slit lamp; common testing, like corneal topography; and highly specialized tests that are unique to DED, including meibography and tear osmolarity. In a field that is rapidly advancing, we should expect that, at a minimum, everything I have mentioned will be available in newer, more accurate, and more efficient instruments.

What’s next in DED diagnostics? With so much data that can be generated, and so little consensus on how that data connects, I predict that future DED best practices will be driven by artificial intelligence (AI). This could be a standalone instrument with a proprietary metric, like the OMNICAD, or a software solution that is instrument-agnostic, like the CSI Dry Eye Software developed by Karl G. Stonecipher, MD. The golden age of DED care is nigh. OM

References

1. Trattler WB, Majmudar PA, Donnenfeld ED, McDonald MB, Stonecipher KG, Goldberg DF. The prospective health assessment of cataract patients’ ocular surface (PHACO) study: the effect of dry eye. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:1423-1430. Published 2017 Aug 7. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S120159

2. Lemp MA, Crews LA, Bron AJ, Foulks GN, Sullivan BD. Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective study. Cornea. 2012;31(5):472-478. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e318225415a

3. Sullivan BD, Palazón de la Torre M, Yago I, et al. Tear film hyperosmolarity is associated with increased variation of light scatter following cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:2419-2426. Published 2024 Aug 28. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S484840