ICD-10 and diabetes: Time to dig deeper

How to navigate the nuanced coding for patients with diabetes.

By René Luthe, Senior Associate Editor

In researching this article on ICD-10 and diabetes-related eye diseases, I heard two statements sure to strike dread into the hearts of ophthalmologists everywhere: “Nothing in ICD-10 is as challenging as patients with diabetes.” And “The fact is that everyone in ophthalmic practice sees people with diabetes.”

Of course, courtesy of Congress, the new coding system has been delayed until 2015. Even with this reprieve, however, physicians should begin preparations; transition always takes longer than you think. Chances are you’ve already learned that under ICD-10, codes are more numerous than ICD-9 and more granular. ICD-10 guidelines also instruct coders to attend to combination codes. These employ a single code for two diagnoses, or a single code for a diagnosis with an associated secondary process.

IT’S COMPLICATED

Incorporating multitudes

What makes coding for diabetes-related eye diseases more challenging is that the coder must consider a relative multitude of factors. The type of diabetes, use of insulin, presence of retinopathy and of proliferation, severity — and then some — all must be reflected in the code you choose.

Take our QUICK POLL

How would you characterize your practice’s preparations for the Oct. 1 changeover to ICD-10?

www.ophthalmologymanagement.com.

The upshot, says Kevin Corcoran, COE, CPC, CPMA, FNAO, president of Corcoran Consulting Group is, “With diabetes, the number of combinations and permutations is more numerous than in years past.”

Think outside the chapter

In addition to this intricacy, consider that the codes you will need to document diabetes-related problems are not all in one chapter of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. Most ophthalmic codes are found in chapter 7, “Eye and Adnexa,” but practices will need to consult chapter 4 as well, where diabetes falls under endocrinic, nutritional and metabolic diseases.

According to Rajiv Rathod, MD, MBA, a board member of the American Academy of Ophthalmic Executives, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Young Ophthalmologist Champion for ICD-10, ophthalmologists will need to research four chapters of the new manual for ICD-10 coding.

Feeling stressed yet? Take heart. While the “there’s-an-app-for-that” approach won’t quite cut it, coding veterans have a plan to lead you to clarity — and to appropriate reimbursements.

The potential for problems

Because ICD-10 requires more specificity for diabetes-related eye diseases than ICD-9, don’t expect cross-walking — the process of matching up codes between the code sets — to be an effective strategy, according to Mr. Corcoran. “There are too many elements to code under ICD-10,” he says.

Will EHR software provide users with the appropriate ICD-10 code or codes based on the information in the medical record? Sometimes, but Mr. Corcoran thinks that ICD-10 coding in challenging situations such as diabetes will dazzle the user with so many code possibilities that ophthalmologists and staff will be thoroughly irritated. “EHR software will throw up a gazillion possible codes, which will annoy the user and lead to errors because users will not take the time to discriminate which one is correct,” Mr. Corcoran says.

ICD-10 training resources

Should all this make you feel the need for some ICD-10 training, here are some options available to physicians and staffs.

• The Academy offers a teaching module and an eye-care-specific reference book, so ophthalmologists don’t have to waste time perusing the whole ICD-10 manual, with its 69,000 codes. Ophthalmology is the only specialty in medicine that has created it’s own ICD-10 reference, Ms. Vicchrilli points out. “We’ve already sold out of it once, but we’ve reordered and we have a fresh supply available online.” It’s available at http://store.aao.org.

• Corcoran CCG is partnering with the American Society of Ophthalmic Administrators for full-day workshop on ICD-10 at the upcoming ASCRS/ASOA meeting in Boston (April 25). Information is available at http://tinyurl.com/CorcoranAOSAICD10.

• UASI, a national provider of medical coding and health information management services, and American Health Information Management Association also provide specialty-specific training designed to be compatible with an ophthalmologist’s busy schedule. Information is available at www.uasisolutions.com or www.ahima.org, respectively.

While the right EHR systems can help, he stresses that an educated user is required to understand which of the many code choices is correct. “Over reliance on the computer system to select an appropriate code is just as bad as giving a calculator to a grammar school student to solve math problems when the child hasn’t learned how to add, subtract, multiply and divide,” says Mr. Corcoran. So there’s no getting around it: Diabetic coding under ICD-10 requires some training.

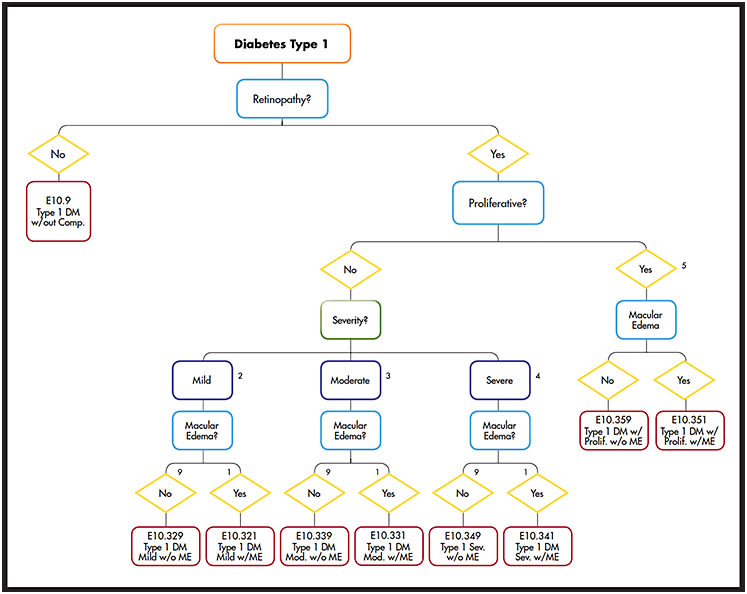

The Academy’s ICD-10 decision tree for type 1 diabetes. The full decision tree is available at tinyurl.com/AAO-ICD10-FlowChart.

COURTESY: AMERICAN ACADEMY OF OPHTHALMOLOGY

WHERE DO YOU START?

First, know the cause

To get your diabetic coding right within ICD-10 requires you to document the underlying cause of the disease. Kathy DeVault, manager at UASI, a coding and health-care consultancy in Cincinnati, explains that under the new coding system, five options exist for type of diabetes: type 1, type 2, drug- or chemical-induced, diabetes due to underlying conditions, and “other.”

Differentiating between type 1 and 2 diabetes will be essential, Mr. Corcoran says. Ms. DeVault concurs. “Instead of having a fifth digit like we do in ICD-9 that identifies type 1 or type 2, they will have their own categories: Type 1 is its own category, type 2 is its own, etc.,” Ms. DeVault explains.

The clinician cannot just write “diabetes mellitus” anymore, Mr. Corcoran says. “That won’t be sufficient to get a code. Your poor biller will be stuck. You’ll get the chart back with a note requesting clarification.”

Once you’ve answered the first, crucial question about the nature of the patient’s diabetes, you may go on to the other questions ICD-10 requires, ones more traditionally the province of the ophthalmologist. These include damage to the eye itself, Mr. Corcoran explains: the location (macula or retina) and severity. The answers will make up the six-digit code for diabetes-related eye disorders.

“Coding is telling a story, and we want to make sure we tell the right story and the full breadth of the story,” Ms. DeVault explains. Thus it is critical the provider accurately portray the patient’s condition. Of course, accurate, thorough coding translates to appropriate reimbursement.

The decision tree

To help you negotiate this battery of questions and construct a code that will get you reimbursed, the Academy has devised a flow chart (Figure). The first step, again, is determining whether the patient’s diabetes is type 1 or type 2. The next question addresses the presence of retinopathy.

“If retinopathy is not present, then the simple code for type 1 without any complications is E 10.9, whereas for type 2, it’s E 11.9,” Dr. Rathod explains.

Next, the clinician must decide, and document in the chart, whether the disease is proliferative or nonproliferative in nature. If it is non-proliferative, is it severe, mild or moderate?

“The next decision within all those subcategories is to determine if there’s macular edema,” Dr. Rathod says. That enables you determine the final code. “It’s easy to see in a flow-chart format the AAO has put together what the appropriate code should be based on the exam findings.”

Sue Vicchrilli, COT, OCS, coding executive with the AAO, believes the decision tree will be invaluable in helping ophthalmologists code correctly. “We recommend physicians print it, perhaps have it laminated — because it will be well worn — and have a copy of it in each lane, the nurses’ station and the billing department as well.”

WHERE ERRORS ARE LIKELY

DME, sub-coding, insulin use

Dr. Rathod points out that even following the decision tree, ophthalmologists will be faced with some confusion. “The codes are very similar until you reach the point of deciding whether the patient has macular edema,” he says. “It’s just one digit that differentiates it.” He says it is crucial clinicians remember that the claim must state whether or not the patient has macular edema, “because that’s either going to be omitted or coded in error. That will probably be one of the biggest sources of error.”

Sub-coding within the severity of the nonproliferative form of the disease will be another source of confusion, Dr. Rathod believes. “Then clinicians have to differentiate that versus proliferative disease,” he says.

As for insulin use, Ms. Vicchrilli reports that many payers probably will not require the clinician to address that question to receive payment. However, for those who do choose to document it, they will find the code in another chapter of the ICD-10 manual. “It’s Z79.4. That is in chapter 21: Factors influence seen health status and contact with health services,” she says.

Forget laterality

Another issue where the Academy anticipates ophthalmologists will encounter difficulty is that in diabetes coding, not every diagnosis is identified by eye. The laterality essential to glaucoma coding is not applicable in diabetes. “In ICD-10, for many eye codes, there’s a digit at the end which will indicate right eye, left eye or both eyes,” Dr. Rathod says. “But for the diabetes eye codes, those are not included. You code just the disease.”

Ms. Vicchrilli adds an example: “If the patient has type 2 diabetes without retinopathy, it’s 11.9; when that’s in the right eye, the physician wants to put a 1 at the end of the code, indicating it’s in the right eye. But that’s not a recognizable code.” That code would not be reimbursed. The patient can have conditions in each eye, but the physician does not document by which eye, but just by the condition.

Improve your detective skills

The Academy’s decision tree makes it clear that ophthalmologists must take a more extensive patient history than many had previously. “ICD-10 really raises the bar in terms of the chart documentation that’s required,” says Mr. Corcoran.

Not only do clinicians and staff need training about the importance of asking more detailed questions of patients, they will also need to learn ways of dealing with patients who don’t want to answer. Some patients will shrug off questions about what type of diabetes they have, or their insulin use, thinking their eye doctor doesn’t need to know these things. Says Mr. Corcoran, “It’s a rather arduous process to fill out that history form, so patients abbreviate; they skip things. When they do that, they provide incomplete information.”

What should the medical assistant or technician do then? They, or the doctor, must make further inquiries. “If the doctor or staff doesn’t do it, and this chart makes it to the billing office, what does the billing office do? They hand the chart back to the doctor, because they can’t code it,” Mr. Corcoran explains. To prevent this from happening in your practice, some tenacity and patient education will be in order. As Mr. Corcoran warns, “You can’t code what’s not in the chart!” And if it’s not coded, you won’t get reimbursed. OM