Treatment Pulse

Diagnosing and Treating Herpetic Infection

Evaluating a selective antiviral that resolves infection with a low toxicity profile

Special Section Sponsored By Bausch + Lomb

with Penny Asbell, MD; Edward J. Holland, MD; Jay Pepose, MD, PhD; John Sheppard, MD

Dr. Holland: Herpes simplex is one of the more challenging conditions we face, from both an infectious and an inflammatory perspective. First, I'd like to talk about the different clinical presentations of herpes simplex virus (HSV). Then we'll talk about treatment approaches.

Epidemiology and Clinical Features

Dr. Holland: A variety of herpetic viruses infect the eye. We're going to focus primarily on herpes simplex virus, and particularly the extremely common HSV type 1. In the United States, about 25% of individuals are seropositive for HSV by the age of 4, and about 100% are positive by age 60. HSV types 1 and 2 and herpes zoster can cause herpetic keratitis, while HSV type 1 causes most ocular lesions.1

Ocular herpes is the leading infectious cause of blindness in the United States. An estimated 400,000 Americans have had some form of ocular infection with HSV, and 20,000 new primary cases of herpetic keratitis are diagnosed each year along with an estimated 28,000 relapses.1

The patient who presents with herpetic eye disease typically follows a pattern of primary outbreak and subsequent reactivation. When the primary outbreak occurs in children, the parents usually don't recognize that the child has been exposed to HSV. The child may have flu-like symptoms, and most of the time, there isn't a clinical eruption. Rarely, children may have disseminated dermatologic HSV, and these children may become quite ill.

After primary infection, the virus becomes latent in the trigeminal ganglion or cornea, where it can be reactivated by stress, ultraviolet radiation or hormonal changes. Lesions are also common in immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV or a recent organ transplant.

The clinical presentation of the keratitis can follow one of four HSV clinical pictures. Patients may have infectious epithelial keratitis, neurotrophic keratopathy, immune stromal keratitis—which is the leading reason for penetrating or lamallar keratoplasty—or a more unusual presentation, such as endotheliitis.

HSV Epithelial Keratitis

Dr. Holland: Infectious epithelial keratitis can present with one of four different lesions: cornea vesicles, dendritic ulcer, geographic ulcer or marginal ulcer. The earliest lesion, cornea vesicles, demonstrates minute, raised, clear vesicles that resemble the vesicular eruptions seen in the skin or mucous membranes (Figure 1). There's no staining early in the process. Of course, the vesicles contain active virus. Many clinicians don't see this vesicular change because by the time and formed a dendritic ulcer.

Because of this rapid coalescence, the most common presentation of infectious HSV keratitis is the dendritic ulcer (Figure 2a). We see this ulcer often—a branching, linear, infectious lesion with terminal bulbs and swollen epithelial borders, containing active virus. It's a true ulcer, since it extends through basement membrane.

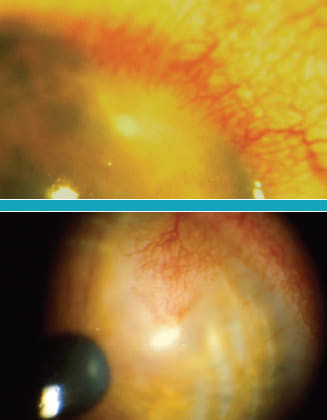

Cornea Vesicles

Figure 1. Infectious keratitis can present with one of four different lesions: cornea vesicles, dendritic ulcer, geographic ulcer or marginal ulcer. The earliest infectious epithelial lesions are cornea vesicles. These lesions demonstrate minute, raised, clear vesicles that correspond to the vesicular eruptions seen in the skin or mucous membranes.

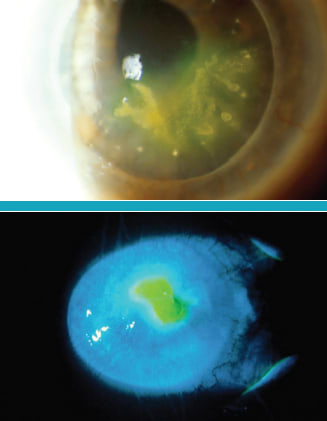

Infectious Epithelial Keratitis: Dendritic and Geographic Ulcers

Figure 2a (top). A dendritic ulcer is a branching, linear infectious lesion with terminal bulbs and swollen epithelial borders. Figure 2b (bottom). A geographic ulcer is an enlarged dendritic ulcer that is no longer linear. The scalloped epithelial borders contain active virus.

When the enlarging dendritic ulcer has a geographic appearance, we call it a geographic ulcer (Figure 2b). The ulcer is no longer linear, and the scalloped epithelial borders contain active virus.

I think a confusing lesion is the marginal ulcer. We're all used to that central or paracentral lesion. We don't see a great deal of inflammation in the early stages, but we see a peripheral dendritic infectious lesion and the dilated limbal vessels adjacent to it, which cause rapid white blood cell infiltrate and a stromal infiltrate underlying the ulcer and adjacent limbal injection. These findings can be confused with the inflammatory marginal ulcer due to blepharitis.

Dr. Sheppard: I think that's a great point. Many patients with what appears to be isolated epithelial disease also have underlying stromal inflammation, and the distinction is never night-and-day. Similarly, the classic location for a dendrite is central, and we're accustomed to the manifestations on the epithelium of a central lesion. A limbal lesion is adjacent to the vascular and lymphocytic arcade in the conjunctiva, and thus much more exposed to the immune response. Thus, the appearance of this lesion is very different. And we may correctly think of staph marginal keratitis first. In a patient with a previous history or other central lesions that suggest herpetic disease, we have to be very careful when managing the inflammatory component (Figure 3).

Infectious Epithelial Keratitis: Marginal Ulcer

Figure 3. Another manifestation of HSV infectious epithelial keratitis is the marginal ulcer. This lesion results from a dendritic ulcer with close proximity to the limbus. The limbal blood vessels result in a rapid infiltration of white blood cells thus resulting in a stromal infiltrate underlying the ulcer and adjacent limbal injection.

Dr. Holland: After patients are treated for infectious dendritic lesions, they may develop persistent dendritic epitheliopathy. This neurotrophic change in the epithelium takes several weeks to resolve.

Sometimes, we see the branching lesion with a dendritic shape on the epithelium, so we continue antiviral treatment. We may even think the dendritic lesion has persisted and progressed to a geographic ulcer, perhaps because we're so used to thinking about the shape of the lesion. But it's not an infectious viral lesion, it's neurotrophic disease. The infection is gone, so the eye doesn't need more anti-infective treatment.

Dr. Pepose: I think that, in the past, prolonged use with topical antivirals had the potential to cause toxicity. Therefore, by continuing therapy, we were potentially causing more damage. We have to recognize the primary cause and identify what we're seeing, not base our decision on the shape.

Dr. Holland: If you're treating a patient with a topical antiviral beyond 2 weeks, you should rethink your diagnosis. An infectious lesion usually doesn't persist that long. It's rare we need to treat more than 2 weeks, unless a patient is immunosuppressed.

In my clinic, the number one reason patients come back month after month is that they develop the next common finding, herpetic or immune (interstitial) stromal keratitis.

Dr. Asbell: Immune stromal keratitis is the form of HSV keratitis that we're most concerned about, since it is persistent. More importantly, it may lead to corneal scarring and permanent loss of vision.

Dr. Holland: The presentation for herpetic immune stromal keratitis includes some or all of the following findings: hazy cornea, active white infiltrate, secondary neovascularization, an immune ring and typically an intact epithelium.

HSV neurotrophic keratopathy

Figure 4. Every dendritic ulcer leads to some findings of dendritic epitheliopathy. As the virus is eliminated and the lesion heals, the dendritic shape persists as a neurotrophic change in the epithelium that takes several weeks to resolve.

Many patients with immune stromal keratitis have a history of a dendritic or geographic ulcer. In fact, 20% to 30% of patients with a dendritic ulcer will develop an immune stromal reaction due to recurrent infection within 5 years of their last dendritic or geographic ulcer.1 However, patients may present to you for the first time with no history of a herpetic lesion because either they don't know they had one or they're in the idiopathic category, and subsequently they'll present with a dendritic ulcer months or years after the stromal disease.

The thought is that these patients have retained viral antigen in the stroma, now eliciting a chronic inflammatory reaction. If we can decrease the viral load faster and eliminate the virus, we may be able to reduce the risk of stromal keratitis.

Dr. Pepose: In the past, we only had the older antivirals and debridement, which had the same underlying principle. We were trying to reduce the antigenic load so we didn't wind up with stromal keratitis or, even worse, necrotizing keratitis. I think the faster we can do something that terminates replication, the better off our patients will be.

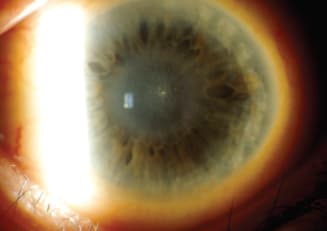

Immune stromal keratitis and endotheliitis

Figure 5. HSV immune stromal keratitis also referred to as interstitial keratitis is thought to be caused by viral antigen retained in the stroma or by the host antigen that is altered by the viral replication.

This is an immunologic reaction that can occur in patients with a dendritic ulcer.

Dr. Asbell: We certainly want to stay on top of these patients because of the risk of scarring. Keep the eye quiet, reduce the inflammation, and treat them aggressively when the dendritic ulcers appear. Some of the patients end up on oral antivirals to control the reactivation. They're the difficult ones who continue to be a challenge.

Dr. Holland: One of the least common but very devastating presentations is necrotizing stromal keratitis. In this situation, there is rapid necrosis of the stroma, possibly due to active viral replication with a massive inflammatory reaction. These patients go on to perforation and often require therapeutic keratoplasty. Fortunately, it's very rare, but it should be understood in the differential diagnosis of herpetic keratitis (HK). The appearance is unmistakable, with necrotic stromal infiltrate, epithelial defect, thinning or melting and perforation.

That brings us to the fourth presentation of herpetic keratitis: endotheliitis. We must be aware of these patients because they can go on to endothelial loss and corneal edema. These patients have keratic precipitates either in a disk shape, a line or diffusely, so you'll see different clinical patterns. There is profound stromal and epithelial edema, which in disciform cases is in a central or paracentral disc-shaped area, and the keratic precipitates correspond to the edema.

These patients have a concomitant iritis, and they can have a trabeculitis and severely elevated IOP at the same time.

Treatment Options for HK (dendritic ulcers)

Dr. Asbell: When we talk about treatment for HSV infection, we know we want to treat with active viral medication. On the other hand, we also want to protect that surface because herpes interferes with the quality of the surface, and we don't want to cause healing problems. We want to eliminate the virus and allow the surface to heal. Your choice for treatment certainly depends on the clinical presentation, but it also depends on your evaluation of how best to protect that surface. We also consider whether the patient will do best with a topical or systemic medication, and we take into account the toxicity associated with various treatments.

HSV Necrotizing Stromal Keratitis

Figure 6. This is a rare form of stromal keratitis called necrotizing stromal keratitis in which there is a rapid viral replication within the stroma and a massive immune reaction that can quickly lead to melting and perforation.

One of the treatment standbys, particularly in the United States, has been trifluridine (Viroptic). Trifluridine is non-selective, so it is activated in both virus-infected cells and normal, healthy cells, which may lead to epitheliopathy and surface problems in some patients.

Dr. Asbell: In addition to old treatment standbys, we also have what I think is a very exciting opportunity to treat our patients effectively and safely. The medication is called ganciclovir ophthalmic gel 0.15% (Zirgan). Ganciclovir has been around a while, used intravitreally and systemically for CMV retinitis, but this topical application was recently approved in the United States for treating ocular herpes. This topical gel is indicated for the treatment of acute herpetic ulcers (dendritic ulcers).

Important Risk Information for ZIRGAN

ZIRGAN (ganciclovir ophthalmic gel) 0.15% is indicated for topical ophthalmic use only. Patients should not wear contact lenses if they have signs or symptoms of herpetic keratitis or during the course of therapy with ZIRGAN. Most common adverse events reported in patients were blurred vision (60%), eye irritation (20%), punctate keratitis (5%) and conjunctival hyperemia (5%). Please see the brief summary of the ZIRGAN full prescribing information provided at the end.

Treating with Ganciclovir

Although in vitro activity doesn't necessarily predict clinical activity, ganciclovir has shown in vitro activity against six herpes viruses. The key is that ganciclovir inhibits the synthesis of viral DNA in two ways. One, it inhibits viral DNA polymerase, stopping replication. Second, it blocks the chain of DNA synthesis by incorporating itself into viral DNA.

Disciform Endotheliitis

Figure 7. Isolated stromal edema with keratic precipitates (KP) is characteristic of endotheliitis. The term disciform causes confusion because many clinicians use the term interchangeably when referring to stromal keratitis and disciform edema.

Ganciclovir effectively kills the virus, but it does so selectively. It can only achieve the two-part process when the drug is activated, and it is selectively activated by viral thymidine kinase. Healthy cells do not selectively activate ganciclovir, so it does not kill or damage them. Clearly, this means that ganciclovir provides us an effective drug that attacks the virus but does not destroy healthy corneal cells. The medication presents an exciting option for practitioners as we balance the virus killing power with epithelial healing. For patients with ocular HSV infections, ganciclovir provides a treatment that can help many patients.

Reference

1. Holland EJ, Schwartz GS, Neff KD. Herpes Simplex Keratitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ and Holland EJ, ed. Cornea 3rd Edition. St Louis: Mosby Year Book Publishers; 2010.

Dr. Asbell is a Professor of Ophthalmology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City and Director of its Cornea Service and Refractive Surgery Center.

Dr. Holland is Director or Cornea Services at the Cincinnati Eye Institute and Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati.

Dr. Pepose is the Founder and Medical Director of the Pepose Vision Institute in St. Louis, Mo. He also serves as Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo.

Dr. Sheppard is President of Virginia Eye Consultants, based in Norfolk, Clinical Director of the Thomas R. Lee Center for Ocular Pharmacology, and Professor of Ophthalmology and Microbiology at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

BAUSCH+LOMB

Zirgarn®

ganciclovir ophthalmic gel 0.15%

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all of the information needed to use ZIRGAN® safely and effectively.

See full prescribing information for ZIRGAN.

ZIRGAN (ganciclovir ophthalmic gel) 0.15%

Initial U.S. approval: 1989

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

ZIRGAN is a topical ophthalmic antiviral that is indicated for the treatment of acute herpetic keratitis (dendritic ulcers). (1)

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

The recommended dosing regimen for ZIRGAN is 1 drop in the affected eye 5 times per day (approximately every 3 hours while awake) until the corneal ulcer heals, and then 1 drop 3 times per day for 7 days. (2)

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

ZIRGAN contains 0.15% of ganciclovir a sterile preserved topical ophthalmic gel. (3)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

None.

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

• ZIRGAN is indicated for topical ophthalmic use only. (5.1)

• Patients should not wear contact lenses if they have signs or symptoms of herpetic keratitis or during the course of therapy with ZIRGAN. (5.2)

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Most common adverse reactions reported in patients were blurred vision (60%), eye irritation (20%), punctuate keratitis (5%), and conjunctival hyperemia (5%). (6)

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Bausch & Lomb at 1-800-323-0000 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

See 17for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION.

Revised: June 2010

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: CONTENTS*

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Topical Ophthalmic Use Only

5.2 Avoidance of Contact Lenses

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

8.3 Nursing Mothers

8.4 Pediatric Use

8.5 Geriatric Use

11 DESCRIPTION

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, and Impairment of Fertility

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

*Sections or subsections omitted from the full prescribing information are not listed.

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

ZIRGAN (ganciclovir ophthalmic gel) 0.15% is indicated for the treatment of acute herpetic keratitis (dendritic ulcers).

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

The recommended dosing regimen for ZIRGAN is 1 drop in the affected eye 5 times per day (approximately every 3 hours while awake) until the corneal ulcer heals, and then 1 drop 3 times per day for 7 days.

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

ZIRGAN contains 0.15% of ganciclovir in a sterile preserved topical ophthalmic gel.

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

None.

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Topical Ophthalmic Use Only

ZIRGAN is indicated for topical ophthalmic use only.

5.2 Avoidance of Contact Lenses

Patients should not wear contact lenses if they have sign or symptoms of herpetic keratitis or during the course of therapy with ZIRGAN.

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

Most common adverse reactions reported in patients were blurred vision (60%), eye irritation (20%), punctuate keratitis (5%), and conjunctival hyperemia (5%).

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy: Teratogenic Effects

Pregnancy Category C: Ganciclovir has been shown to be embryotoxic in rabbits and mice following intravenous administration and teratogenic in rabbits. Fetal resorptions were present in at least 85% of rabbits and mice administered 60 mg/kg/day and 108 mg/kg/day (approximately 10,000x and 17,000x the human ocular dose of 6.25 mcg/kg/day), respectively, assuming complete absorption. Effects observed in rabbits included: fetal growth retardation, embryolethality, teratogenicity, and/or maternal toxicity. Teratogenic changes included cleft palate, anophthalmia/microphthalmia, aplastic organs (kidney and pancreas), hydrocephaly, and brachygnathia. In mice, effects observed were maternal/fetal toxicity and embryolethality. Daily intravenous doses of 90 mg/kg/day (14,000x the human ocular dose) administered to female mice prior to mating, during gestation, and during lactation caused hypoplasia of the testes and seminal vesicles in the month-old male offspring, as well as pathologic changes in the nonglandular region of the stomach (see Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, and Impairment of Fertility).

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. ZIRGAN should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

8.3 Nursing Mothers

It is not known whether topical ophthalmic ganciclovir administration could result in sufficient systemic absorption to produce detectable quantities in breast milk. Caution should be exercised when ZIRGAN is administered to nursing mothers.

8.4 Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy in pediatric patients below the age of 2 years have not been established.

8.5 Geriatric Use

No overall differences in safety or effectiveness have been observed between elderly and younger patients.

11 DESCRIPTION

ZIRGAN (ganciclovir ophthalmic gel) 0.15% contains a sterile, topical antiviral for ophthalmic use. The chemical name is 9-[[2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethoxy]methyl]guanine (CAS number 82410-32-0). Ganciclovir is represented by the following structural formula:

Ganciclovir has a molecular weight of 255.23, and the empirical formula is C9H13N504.

Each gram of gel contains: ACTIVE: ganciclovir 1.5 mg (0.15%). INACTIVES: carbopol, water for injection, sodium hydroxide (to adjust the pH to 7.4), mannitol. PRESERVATIVE: benzalkonium chloride 0.075 mg.

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

ZIRGAN (ganciclovir ophthalmic gel) 0.15% contains the active ingredient, ganciclovir, which is a guanosine derivative that, upon phosphorylation, inhibits DNA replication by herpes simplex viruses (HSV). Ganciclovir is transformed by viral and cellular thymidine kinases (TK) to ganciclovir triphosphate, which works as an antiviral agent by inhibiting the synthesis of viral DNA in 2 ways: competitive inhibition of viral DNA-polymerase and direct incorporation into viral primer strand DNA, resulting in DNA chain termination and prevention of replication.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

The estimated maximum daily dose of ganciclovir administered as 1 drop, 5 times per day is 0.375 mg. Compared to maintenance doses of systemically administered ganciclovir of 900 mg (oral valganciclovir) and 5 mg/kg (IV ganciclovir), the ophthalmically administered daily dose is approximately 0.04% and 0.1% of the oral dose and IV doses, respectively, thus minimal systemic exposure is expected.

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, and Impairment of Fertilty

Ganciclovir was carcinogenic in the mouse at oral doses of 20 and 1,000 mg/kg/day (approximately 3,000x and 160,000x the human ocular dose of 6.25 mcg/kg/day, assuming complete absorption). At the dose of 1,000 mg/kg/day there was a significant increase in the incidence of tumors of the preputial gland in males, forestomach (nonglandular mucosa) in males and females, and reproductive tissues (ovaries, uterus, mammary gland, clitoral gland, and vagina) and liver in females. At the dose of 20 mg/kg/day, a slightly increased incidence of tumors was noted in the preputial and harderian glands in males, forestomach in males and females, and liver in females. No carcinogenic effect was observed in mice administered ganciclovir at 1 mg/kg/day (160x the human ocular dose). Except for histocytic sarcoma of the liver, ganciclovir-induced tumors were generally of epithelial or vascular origin. Although the preputial and clitoral glands, forestomach and harderian glands of mice do not have human counterparts, ganciclovir should be considered a potential carcinogen in humans. Ganciclovir increased mutations in mouse lymphoma cells and DNA damage in human lymphocytes in vitro at concentrations between 50 to 500 and 250 to 2,000 mcg/mL, respectively.

In the mouse micronucleus assay, ganciclovir was clastogenic at doses of 150 and 500 mg/kg (IV) (24,000x to 80,000x human ocular dose) but not 50 mg/kg (8,000x human ocular dose). Ganciclovir was not mutagenic in the Ames Salmonella assay at concentrations of 500 to 5,000 mcg/mL.

Ganciclovir caused decreased mating behavior, decreased fertility, and an increased incidence of embryolethality in female mice following intravenous doses of 90 mg/kg/day (approximately 14,000x the human ocular dose of 6.25 mcg/kg/day). Ganciclovir caused decreased fertility in male mice and hypospermatogenesis in mice and dogs following daily oral or intravenous administration of doses ranging from 0.2 to 10 mg/kg (30x to 1,600x the human ocular dose).

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

In one open-label, randomized, controlled, multicenter clinical trial which enrolled 164 patients with herpetic keratitis, ZIRGAN was non-inferior to acyclovir ophthalmic ointment, 3% in patients with dendritic ulcers. Clinical resolution (healed ulcers) at Day 7 was achieved in 77% (55/71) for ZIRGAN versus 72% (48/67) for acyclovir 3% (difference 5.8%, 95% CI - 9.6%-18.3%). In three randomized, single-masked, controlled, multicenter clinical trials which enrolled 213 total patients, ZIRGAN was non-inferior to acyclovir ophthalmic ointment 3% in patients with dendritic ulcers. Clinical resolution at Day 7 was achieved in 72% (41/57) for ZIRGAN versus 69% (34/49) for acyclovir (difference 2.5%, 95% CI -15.6%-20.9%).

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

ZIRGAN is supplied as 5 grams of a sterile, preserved, clear, colorless, topical ophthalmic gel containing 0.15% of ganciclovir in a polycoated aluminum tube with a white polyethylene tip and cap and protective band (NDC 24208-535-35).

Storage

Store at 15°C-25°C (59°F-77°F). Do not freeze.

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

This product is sterile when packaged. Patients should be advised not to allow the dropper tip to touch any surface, as this may contaminate the gel. If pain develops, or if redness, itching, or inflammation becomes aggravated, the patient should be advised to consult a physician. Patients should be advised not to wear contact lenses when using ZIRGAN.

Revised: June 2010

ZIRGAN is a trademark of Laboratoires Thea Corporation licensed by Bausch & Lomb Incorporated.

© Bausch 8, Lomb Incorporated